The critical role of disinfection in infection prevention: Key takeaways from Professor Karpiński’s lecture with webinar recording

This article is based on the scientific lecture, "Disinfection, key pillar of infection prevention," delivered by Professor Tomasz Karpiński as part of the Arxada Scientific Webinar Series.

The global health community recognizes that we are entering a post-antibiotic era, where the effectiveness of once-revolutionary drugs is critically declining. As experts in professional hygiene, we must move beyond basic cleaning protocols. Effective disinfection is not merely an operational task; it is one of the most powerful combat strategies in preventing the spread of multi-drug resistant organisms (MDROs).

Use of the right products in line with high quality hygiene protocols can directly impact patient safety and can be considered a fundamental step in breaking the chain of infection.

1. The non-negotiable threat: scope of the AMR crisis

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) - the ability of microorganisms to survive in the presence of an antimicrobial agent - is unequivocally one of the top ten greatest global threats to public health.2

The human cost is staggering and demands immediate, rigorous preventive action:

- More than one million people die yearly from infections caused by drug-resistant bacteria. [1]

- It is estimated that MDROs will be responsible for 10 million deaths in 2025 alone, with projections rising to approximately 39 million deaths between 2025 and 2050.[2],[3]

- The spread of MDRO strains, particularly gram-negative bacteria such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, has led to a critical reduction in therapeutic options.[4]

- Pathogens like Candida auris have been designated as a global health threat, with mortality rates ranging from 30% to 70% in infected patients.[5]

| Critical group | High group | Medium group |

|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter baumannii carbapenem-resistant | Salmonella Typhi fluoroquinolone-resistant | Group A Streptococci macrolide – resistant |

| Enterobacterales third-generation cephalosporin-resistant | Shigella spp. fluoroquinolone-resistant | Streptococcus pneumoniae macrolide-resistant |

| Enterobacterales carbapenem-resistant | Enterococcus faecium vancomycin-resistant | Haemophilus influenzae ampicillin-resistant |

| - | Non-typhoidal Salmonella fluoroquinolone-resistant | Group B Streptococci penicillin resistant |

| - | Neisseria gonorrhoeae third-generation cephalosporin, and/or fluoroquinolone-resistant | - |

| - | Staphylococcus aureus methicillin-resistant | - |

- Pathogens like Candida auris have been designated as a global health threat, with mortality rates ranging from 30% to 70% in infected patients.[1]

| Critical group | High group | Medium group |

|---|---|---|

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Nakaseomyces glabrata (Candida glabrata) | Scedosporium spp. |

| Candidozyma auris (Candida auris) | Histoplasma spp. | Lomentospora prolificans |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Eumycetoma causative agents | Coccidioides spp |

2. Disinfection: The essential break in the transmission chain

While strategies like vaccination and reduction of unjustified antibiotic use are critical, they need to go hand in hand with high quality hygiene protocols. Having robust processes for hand hygiene, as well as surface and equipment disinfection, can help to target the silent and persistent reservoirs of pathogens that cause AMR spread and may lead to hard to treat infections.

Reservoirs and biofilm

Environmental surfaces act as crucial reservoirs where MDROs can survive for days to months, significantly increasing the risk of transmission. This includes critical medical devices such as endoscopes, which are known sources of MDRO pathogens.

The most serious threat is biofilm, a complex, three-dimensional structure protecting microorganisms. Biofilm-associated cells can be 1,000 times less sensitive to disinfectants and antibiotics compared to planktonic cells. Disinfection with proven efficacy products is essential to interrupt this cycle by penetrating and disrupting the polysaccharide matrix that shields these pathogens.[6]

Evidence-Based Impact

Effective disinfection is critical in breaking the chain of transmission. Studies show that implementing targeted disinfection protocols lowers MDRO infection rates in healthcare settings, which consequently decreases treatment costs and improves patient outcomes.[7]

3. Technical integrity: Addressing efficacy and adaptation

For disinfection to remain the "most powerful weapon", products must be used correctly, and their efficacy must be unwavering against the challenge of microbial adaptation.

The effectiveness of disinfectants is critically dependent on both time and concentration. Inadequate protocols or mistakes in hygiene plan execution, including insufficient exposure time or too low concentrations, can select for persistent microbes.

The adaptation challenge

Research confirms that bacteria and fungi can undergo a rapid process of adaptation, which can lead to a lack of effectiveness of active substance. This process has been linked to improper use of substances.8

Crucially, some substances demonstrate a very high risk of this adaptation/resistance development[8]:

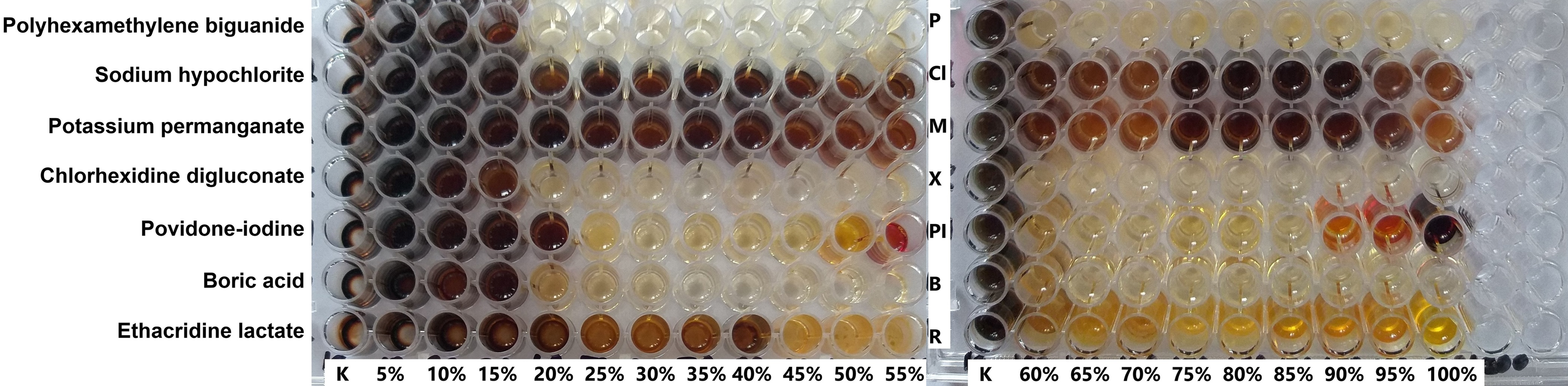

- Studies show that microorganisms can adapt to 100% commercial concentrations of both sodium hypochlorite and potassium permanganate.

- When adaptation reaches the commercial concentration, the product is ineffective, which the presenter calls "resistance".

- This confirms the necessity of using chemistries with a demonstrably low risk of adaptation, as assessed by metrics like the Karpiński adaptation index (KAI).

Picture 1 Pathogen adaptation; The analysis of active substance against Pseudomonas aeruginosa clearly demonstrates that utilizing concentrations below the recommended use-level (100% = commercial/RTU concentration) dramatically increases the microbial adaptation potential. Furthermore, this adaptation can occur with some chemistries even at full concentration (ex. sodium hypochlorite), providing direct evidence that these agents render organisms not sensitive to antiseptics. This underscores the necessity of selecting scientifically proven agents with a multi-target mode of action. Source: Karpiński, T. M., Korbecka-Paczkowska, M., Stasiewicz, M., Mrozikiewicz, A. E., Włodkowic, D., & Cielecka-Piontek, J. (2025). Activity of Antiseptics Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Its Adaptation Potential. Antibiotics, 14(1), 30.

4. The multi-target advantage: utilizing high-level disinfection

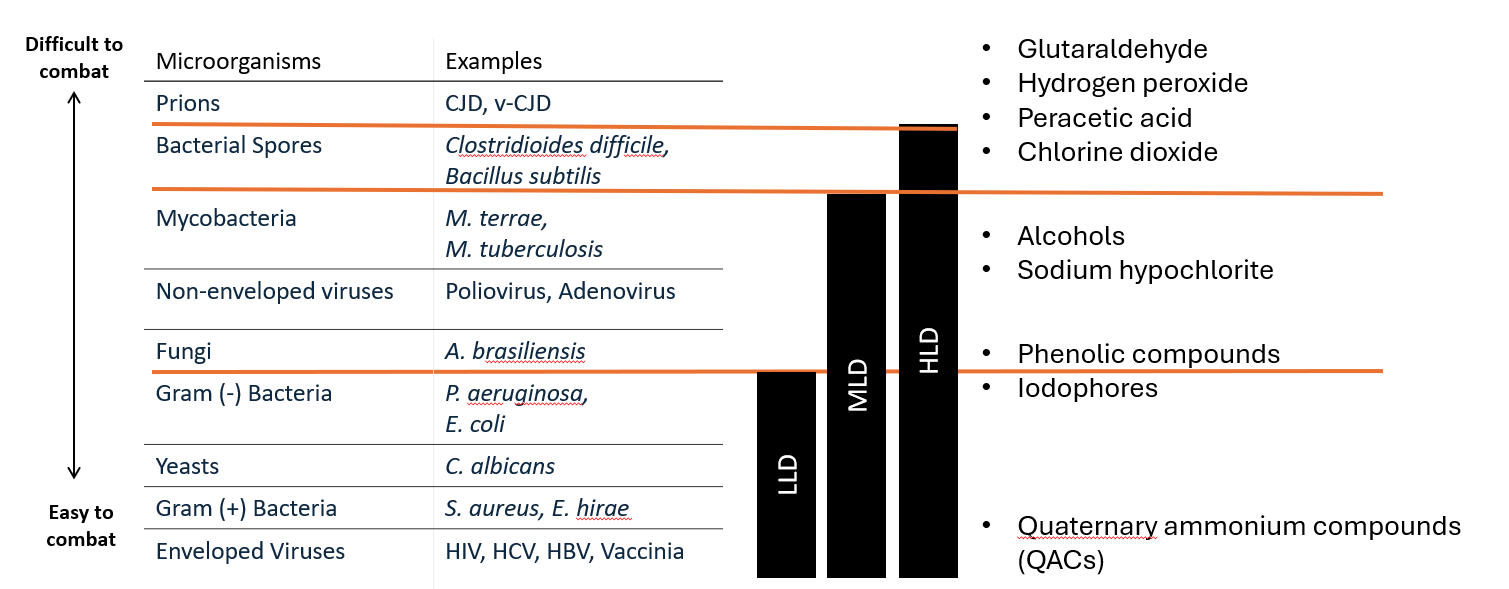

Disinfectants, unlike most antibiotics which act on a single target, often exhibit multi-directional activity against numerous targets within the microbial cell. This mechanism is thought to create a higher energy barrier for microbes, lowering the possibility of adaptation.

For healthcare and medical device reprocessing, High-Level Disinfection (HLD) is non-negotiable, as it is required to act against bacterial spores (e.g., Clostridioides difficile and Bacillus species), mycobacteria, and non-enveloped viruses.

Proven high level disinfection (HLD) solutions for critical scenarios

The potential for bacterial adaptation to antibiotics, antiseptics, and disinfectants is the subject of studies conducted by our scientific team at Poznań University of Medical Sciences. Our work confirms that in critical clinical scenarios, which demand High-Level Disinfection (HLD), the key is to use chemistry with multi-directional mechanisms of action. This approach minimizes the risk of microbial adaptation and is absolutely necessary in the highest-risk areas, such as the reprocessing of reusable medical devices, including endoscopes.

Below, we present proven HLD chemistries that effectively meet the challenges posed by superbugs and spores:

Peracetic acid: this substance effectively acts not only against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae but also against "superbugs" found in endoscopes where biofilm is present.

Chlorine dioxide: A small molecule with multi-directional activity, its strong oxidizing property destroys microbial cell membranes, damages genetic material (especially RNA), and disrupts metabolism. This makes it a good HLD agent that acts strongly against spores and biofilms.

Conclusion: Upholding standards

Effective disinfection is a core pillar of infection prevention. As producers, distributors and healthcare professionals, we must be unwavering in:

- Selection: Choosing chemistries with proven multi-target activity and a low risk of microbial adaptation.

- Compliance: Ensuring strict adherence to manufacturer-recommended contact times and concentrations to prevent the selection of persistent strains.

By prioritizing validated disinfection protocols, we can directly combat the MDRO threat, securing patient safety and sustaining the efficacy of our remaining antibiotic options.

If you would like to see full webinar recording, click the button below.

[1] WHO. Global antibiotic resistance surveillance report 2025.

[2] O’Neill J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations on Antimicrobial Resistance. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Published: May 2016.

[3] Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM) Project. Published: September 16, 2024

[4] World Health Organization (WHO). Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. WHO Press Release, 27 February 2017.

[5] World Health Organization (WHO). WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. WHO, 2022.

[6] Expert Panel Opinion. (2022). Epidemiology, Mechanisms of Resistance and Treatment Algorithm for Infections Due to Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: An Expert Panel Opinion. Antibiotics, 11(9), 1263.

[7] Mitchell, B.G., Browne, K., White, N., et al. Investigating the effect of enhanced cleaning and disinfection of shared medical equipment on health-care-associated infections in Australia (CLEEN): a stepped-wedge, cluster randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2024.

[8] Karpiński, T. M., Korbecka-Paczkowska, M., Stasiewicz, M., Mrozikiewicz, A. E., Włodkowic, D., & Cielecka-Piontek, J. (2025). Activity of Antiseptics Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Its Adaptation Potential. Antibiotics, 14(1), 30.

Featured content

Want to learn more?